A few weeks ago, I had the pleasure of going to see Dylan Wiliam speak at UCL (not that I’ve mentioned it too many times or anything!) This story is however, not about Dylan W. I was sat mingling with the other educators ahead of his talk, when I got into conversation with a lovely lady who’s involved in professional training. She mentioned that she had attended a conference that week and preceded to tell me about a particular speaker at the conference. ‘I’m in my 60s and she made me feel like I could do anything. I used to think that the number of years of experience you had determined how good you were at your job but not anymore…’ She spoke incredibly highly of this speaker, and I was curious to know more. We continued to talk, only for me to discover that by chance I had visited this leaders’ school earlier that week and had the pleasure of hearing from her and being equally inspired by her journey. We were both referring to Thahmina Begum, Executive Headteacher at Forest Gate Community School.

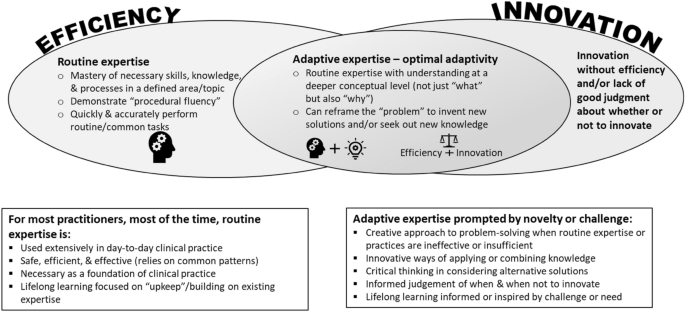

The more I’ve researched, read and explored school leadership and culture, the more inclined I am to avoid narratives of ‘hero leadership’ but I am compelled to tell this story, mostly because I do think there is some value to be derived from looking at the conditions that leaders cultivate and considering what’s contributed to these conditions being instilled in our schools. It’s such a complex and messy business, that when colleagues within the sector are getting it right, I think it’s important we consider why to support the development of our own mental models and adaptive expertise (see below for a useful diagram on the role of adaptive expertise in from the field of Medicine, concerning clinical educators-Cupido, N., Ross, S., Lawrence, K. et al) .I am also a strong advocate of collaborative professional growth so that we can collectively refine our thinking around what ‘best practice’ really means, especially in leadership- a field where research on ‘best bets’ is relatively thin on the ground.

Erhard refers to the distinction between being ‘on the court’ and ‘in the stands’- it is here that I think we can draw value and insight into great leadership- from learning from those who are having impact ‘on the court’.

I want to begin with the end…the culture of continuous improvement that is evidently woven into the tapestry of the school’s very being. I think a true culture of continuous improvement is a lot harder to achieve than one thinks. It goes beyond ‘wanting’ to continuously improve and accepting the importance of continuously improving. And for a leader, this can present a very difficult tension. On the one hand, leaders are presumably hired into leadership role because of their competency, knowledge and skill sets and therefore need to present with a reliability that assures those they lead. On the other hand, they must model how necessary ‘learning’ is at all levels in order to cultivate an authentic and deep culture of continuous improvement. This is one of the key qualities of Thahmina’s that shone through as she discussed the schools’ approach to continuous professional development.

She models continuous learning whilst maintaining a competent and assured position.

This is achieved in a number of ways:

- A commitment to evidence-informed approaches: by being a leader who is constantly engaged with the ‘evidence’, she is able to remover her own self-expression and ‘position’ from the equation. She levels the playing field between herself and those she leads by allowing a focus on the knotty problems of teaching and learning, rather than focusing attention on her own perspective or relative position. Julia Dhar, world debating champion, refers to the idea of separating identity from ideas and how this enables people to more easily access an idea or notion that they can then engage with. It’s not Thahmina’s idea…it’s her professional judgement and context-considerate perspective, guided by the evidence and what educational research tells us are the best bets.

- She engages with the sector in order to share the school’s approaches. In doing so, she vulnerably allows for ‘critical feedback’ knowing that it may challenge her thinking but will ultimately strengthen the approach itself and thus implementation within the school.

- She speaks with authority and assurance, knowing her position is guided by evidence-informed practiced.

She leads with humility and challenges traditional orthodoxies of ‘leadership’.

Beyond her approach in cultivating a culture of continuous improvement, there was one particular thing that struck me (and evidently the lady I struck up a conversation with at the UCL lecture)- her humility. I write this with some hesitation, knowing that humility is a word often thrown around in the leadership sphere…again associated with the hero leadership narrative…and very difficult to pin down!

A Headteacher at 31 and an Executive Headteacher at the age of 35, Thahmina embodies a spirit of humility (not least because her response to this blog was ‘I have lots of brilliant people that make me look good’) and unrelenting high standards which although are opposite in nature, compliment one another and are manifested through:

- An acknowledgement of the role of both intelligent and compassionate accountability in school improvement: on the day we visited Thahmina and her CEO spoke about the ‘soft conversations about what was going wrong’.

- The ability to flip the narrative around teaching and learning so it’s approached with the same urgency and importance as safeguarding- again this is done with a humble purpose and spirit of service with regards to the pupils they work with. It come backs to their ‘why’ and their ability to ensure that it’s fulfilled through a common and shared sense of understanding.

- Clarity about the greater purpose that goes beyond oneself.

An analogy that might clarify this last point is that of the popular gameshow ‘CatchPhrase’. Thahmina sees the bigger picture and communicates this with clarity so that those she leads are able to see their role and part in contributing to that ‘bigger picture’.

Thahmina challenges traditional leadership orthodoxies. She is proof that your age doesn’t constrain your ability to go after the necessary learning experiences to have the competency, confidence, and compassion to lead well. A challenge that I have faced throughout my career, she reminded me that it is not our years of service that define our expertise (although arguably this plays a part) but the substance and quality of our practice and our openness to learning.

I’d like to conclude this blog with a quote from someone whose experience as a Senior Leader has been enriched by Thahmina’s leadership. I do so with the intention to uncover the ‘lived experience’ of those who have worked with her day-in, day-out, as to highlight the impact this remarkable educator has had not only on the outcomes of the young people her schools serve, but also on the colleagues she has led.

‘As my line manager when I was a senior leader at FGCS and then as my Headteacher, Thahmina supported me and challenged me in equal measure. I felt seen, valued and cared for by Thahmina as she gave me the autonomy to run with my ideas, particularly around leading English and T&L, and then challenged me to think differently. Thahmina taught me what effective line management is and really understood my strengths and helped me to close the gaps in my leadership skills. For example, I always struggled to hold people to account and Thahmina taught me about Radical Candour which really empowered me as a new senior leader.

What has been really powerful for me has been seeing Thahmina, as a hijab wearing woman, lead so effectively for the students. I never thought I would want to be a Headteacher but seeing Thahmina lead as a Executive Headteacher inspires me and I hope to be like her one day.’

These stories unveil the amazing work that goes on in corridors and classrooms up and down the country and remind us of what a joy it is to work in the profession amongst talented practitioners and amazing pupils.

Dan Willingham refers to the idea of stories being ‘psychologically privileged’ and off the back of the publication of ‘Building Culture’ I hope to continue to tell the stories of wonderful leaders in schools (who I have the privilege of learning from and speaking with) who are making a difference where it matters- in classrooms and staffrooms. And I would encourage you to share and reflect on these stories too, so that we can collectively shift the negative rhetoric that sometimes casts a shadow amongst our beautiful, vibrant profession.