I recently came across a thought-provoking blog by Nimish Lad on leadership as an attentional practice (link here- https://researcherteacher.home.blog/2025/08/17/leadership-as-an-attentional-practice/) He writes:

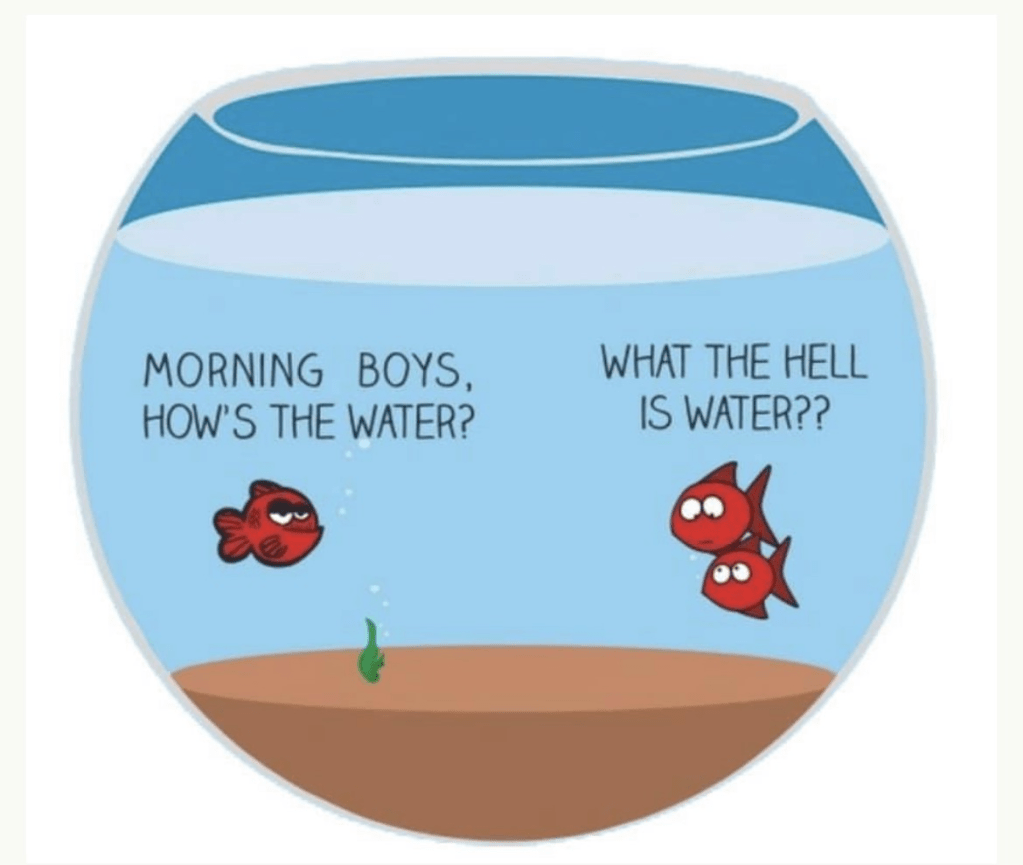

“I am reminded of the phrase ‘you don’t know what you don’t know.’ While reflecting on your own practice is important, it may be more important to seek out the views of others to feedback on what you may not be paying enough attention to.”

That struck me. Leadership, especially in schools, is so often framed as an individual pursuit. We instinctively look for the expert, the decision-maker, the one with the answers. That’s what leaders are for, right?

Traditionally, leadership has been about evaluating the state of play, setting the direction and charting the course. But that model carries an inherent risk: important decisions get made in isolation. When just one or two people make a call, it is inevitably shaped by their assumptions, beliefs, values, and knowledge base.

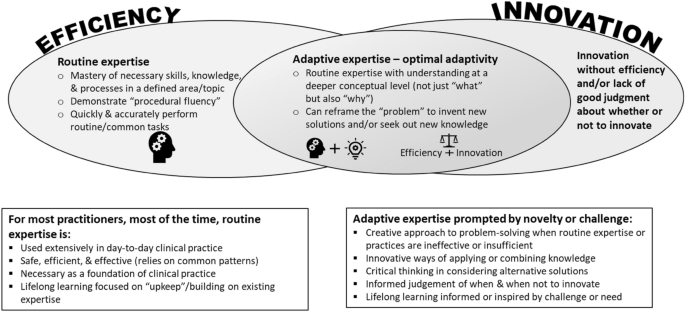

“But they’re the experts,” you might say. “It’s their job to decide.” Perhaps. But as Chi, Glaser, and Farr (1988) remind us: ‘Experts excel mainly in their own domains.’ And even within those domains, expertise is not simply the product of innate talent or accumulated experience. As Ericsson & Ward (2007) define it expertise is: ‘Consistent, superior performance on key tasks, achieved through long-term, structured practice that transforms cognitive and physiological capabilities.’

That’s invaluable when specific knowledge is needed, but much less helpful when tackling complex, school-wide challenges that cut across multiple areas and perspectives. Take, for example, the challenge of improving literacy. While it might seem like the responsibility of the English Lead or Head of English alone, it also falls to the Geography Lead, the Science Lead, and even the Personal Development Lead to address this priority. In these cross-cutting areas, the expertise of each subject leader must be acknowledged and respected. At the same time, pooling this specialised knowledge allows teams to address broader priorities collaboratively, ensuring that decisions benefit from both deep expertise and the diverse perspectives needed for school-wide improvement.

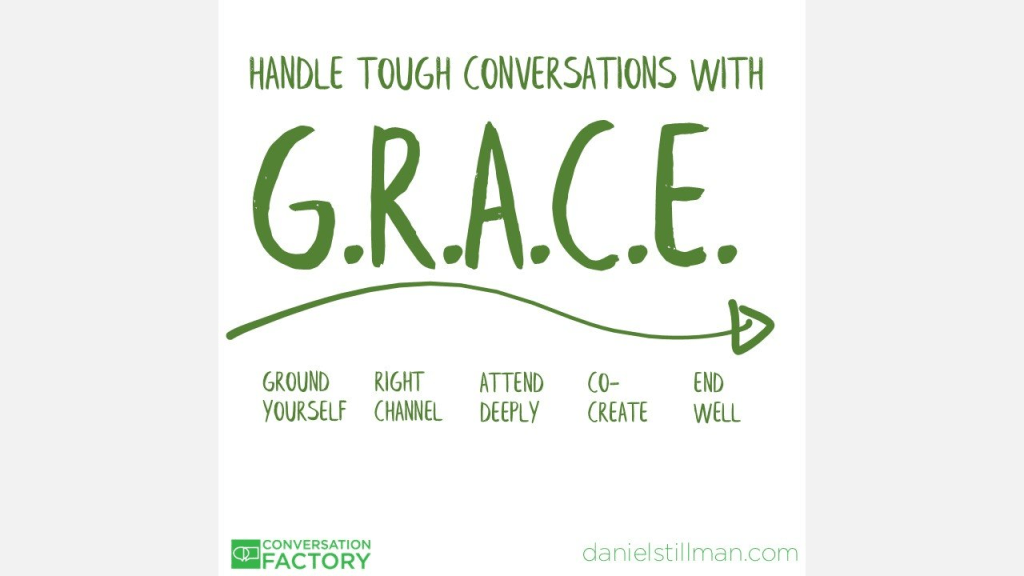

This is where leadership must expand beyond the boundaries of individual expertise. It means stepping outside your own lens of what needs to be done to collaborate on solutions that serve both your area and wider improvement priorities.

Consider another example: senior leaders setting strategic priorities for the year ahead. Say a leader identifies Mathematics as a key area for development. That decision may well have come from deep analysis, looking at assessment data, classroom practice, and work scrutiny. But even then, it’s one person’s interpretation of that evidence, inevitably shaped by their biases, preferences, and prior experience. As Adam Grant puts it: ‘If knowledge is power, knowing what we don’t know is wisdom.’ (Grant, 2021)

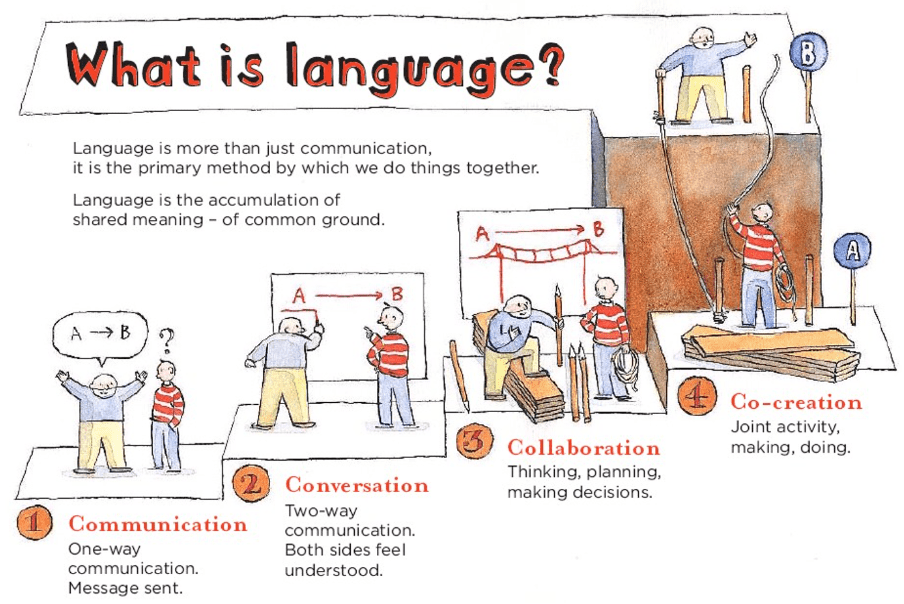

In medicine, high-stakes, complex decision-making is often handled through multidisciplinary teams. These are groups of professionals from different specialties who come together to make decisions for a single patient. The structure of this model is worth examining:

- Expertise is shared across disciplines to make more informed decisions.

- The significance of the decision is explicitly acknowledged.

- Key data and evidence are shared in advance, so everyone comes prepared.

- Deliberate discussion considers risks, benefits, ethical implications, and patient preferences.

- A clear decision is recorded, with a plan for review.

This approach has been shown to promote meaningful collaboration across disciplines and ultimately improve patient outcomes. A 2023 meta-analysis found that interprofessional learning within multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) led to a 23% reduction in treatment-related complications compared to standard care (Reeves et al., 2023).

Of course, none of this is to dismiss the importance of expertise, practicality, or accountability. There are moments when swift, decisive leadership is essential, and times when the responsibility cannot be shared. The buck still stops with the headteacher or senior leader. Nor is it realistic to suggest that schools, already stretched for time, can replicate the full structures of multidisciplinary teams in medicine. The point is not to abandon expertise or delay action, but to balance it: recognising where a leader’s specialist knowledge should guide the way, and where opening the conversation to others can surface blind spots, enrich perspectives, and ultimately lead to wiser decisions.

We’ve seen versions of this approach adopted in education already, in pupil progress meetings or in a pastoral context where multiple agencies come together to consider how best to support a pupil e.g. team around the family. But what if we used this model more intentionally not just for intervention, but to guide strategic decision making as leaders?

What if we made space for genuinely shared sense making, where knowledge is pooled, perspectives are challenged, and blind spots are surfaced before they become missteps? Perhaps leadership is less about having the answers, and more about creating the conditions for better questions and wiser decisions to emerge.

References

- Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R., & Farr, M. J. (1988). The nature of expertise. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Ericsson, K. A., & Ward, P. (2007). Capturing the naturally occurring superior performance of experts in the laboratory: Toward a science of expert and exceptional performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 346–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00533.x

- Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don’t know. Viking.

- Reeves, S., Xyrichis, A., Zwarenstein, M., & et al. (2023). The effectiveness of interprofessional teams: A meta-analysis. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 37(2)