As leaders, we spend a lot of time communicating. Communicating our thoughts. Communicating our feedback. Communicating our relative position on a charted course. Communicating makes up so much of what we do. As school leaders, we work in complex environments that are demanding, unrelenting and require constant communication. Yet, there is little, or no training provided to school leaders on how to get this aspect of leadership right. Instead, we form representations of great communication in our mind; an amalgamation of great and not so great communicators that we’ve experienced and rely on these to help us craft our messages.

The challenge for us leaders is that we often adopt ‘approaches’ to communication that become a trademark of our ways of working. Why might this be problematic? If our mental representation of great communication is ill-informed or if we don’t intentionally set norms around the way we communicate in our teams, we may have an unhelpful reputation on our hands…Introducing…

–The truth teller: the leader who tells the excruciating truth with very direct use of language every single time. You know where you stand but you’re not left standing…you’re left crushed…into a former shadow of your professional self, questioning your value as a human being. Psychological safety might be easier to achieve with this leader at the helm because they are so transparent, but it also might be harder because their direct-ness is intimidating and shuts others down.

–The nice leader: this nice leader is beloved by all. They are easy to talk to and fun to be around, but they prize being liked over everything else. Because of this, you’re not quite sure that what you’re getting is an accurate view of what they truly think. Trust might be more easily achieved with this leader from a relational standpoint but less so from a competency-standpoint. Do I trust this leader to point out my strengths? YES. Do I trust them to tell me the truth about the real state of play? Not so much.

–The dresser up of the truth: this leader uses beautiful and flowery language to dress things up. It sounds kind of wonderful but a dark feeling in the pit of your stomach tells you it’s anything but wonderful. Communication may not seem particularly authentic because it’s had so much ‘work done to it’. Once this happens a few times and we recognise this as a pattern of communication, we may shut down entirely for future interactions.

–The overwhelmed leader: this leader is deeply caring but every conversation appears to evoke a sense of panic in them which in turn evokes panic in you. You are ultra-aware of this leader’s workload and therefore upward empathy is well-established. The downside of this, is that people tend to avoid conversations with them altogether, as to not stress them out.

The four above caricatures of leaders are just that- fairly exaggerated caricatures from the point of view of colleagues in these leaders’ teams. There is also no judgement of these caricatures- it’s likely that as leaders, we’ve all played these parts at some point (I know I have!!). But they do remind us of a few important things:

- Choices we make around the way we communicate come with pros and cons. There’s never a ‘right’ way to do it and context is everything. We may, in certain situations, for example NEED to be ‘the truth teller’. It’s not clear-cut, it’s incredibly nuanced and there’s no ‘educational best bets’ to lean back on around communication- much of this relies on instinct and having experienced or seen good models of communication before.

- Choices we make around how we communicate can very easily morph into these caricature trademarks, which can inadvertently impact our leadership efforts. Being more aware of how we’re communicating and the impact this has on those we lead, is our best bet.

- Recognising that our intentions may be at odds with how our message or story lands for the recipient is crucial.

What communication?

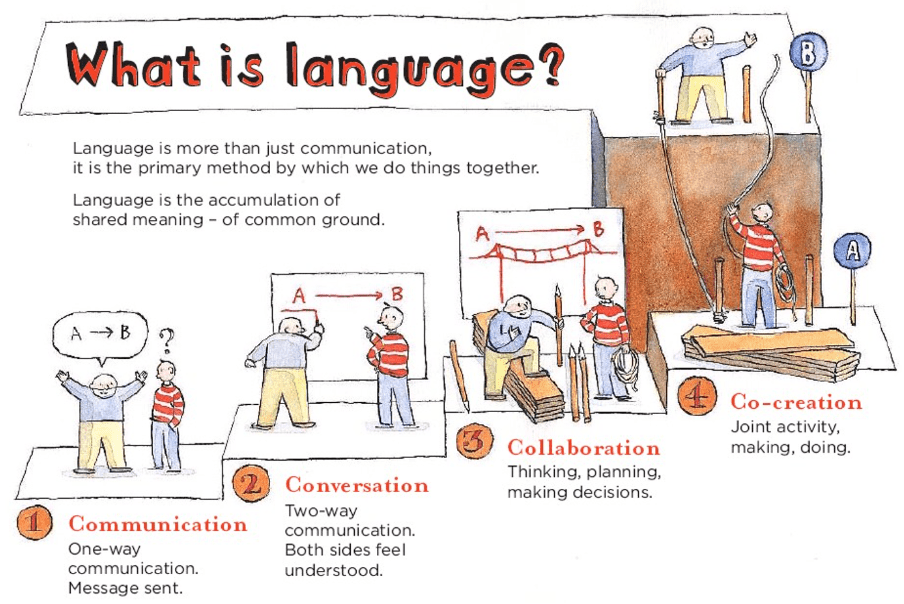

So how might leaders support themselves in crafting their message? To begin with it’s important to boil it down to, as Dave Gray calls it, ‘the primary method by which we do things together’- language. What can language be used for?

- Communication

- Conversation

- Collaboration

- Co-creation

By first, identifying the purpose of what we’re doing together, we can begin to consider the ways in which we might use language to fulfil these purposes.

Language for Communication

Language for collaboration will look markedly different to language for co-creation. Language for collaboration, for example, will be far more tentative, flexible, and fluid. A specific example? Modal verbs will be far more present in our vernacular. ‘This might be the way forward…’ ‘We may need to explore the different approaches further.’

Language for communication, where a message needs to be transmitted from A-B will look slightly different- it will be direct, with imperative verbs, economy of language and crisp clarity. Short prose, with key headlines work very well for this type of communication and in the best-case scenario, there is very little room for interpretation. (NB- also worth noting the visual above and the clarity it brings to this conceptualisation, as a means of communicating an idea).

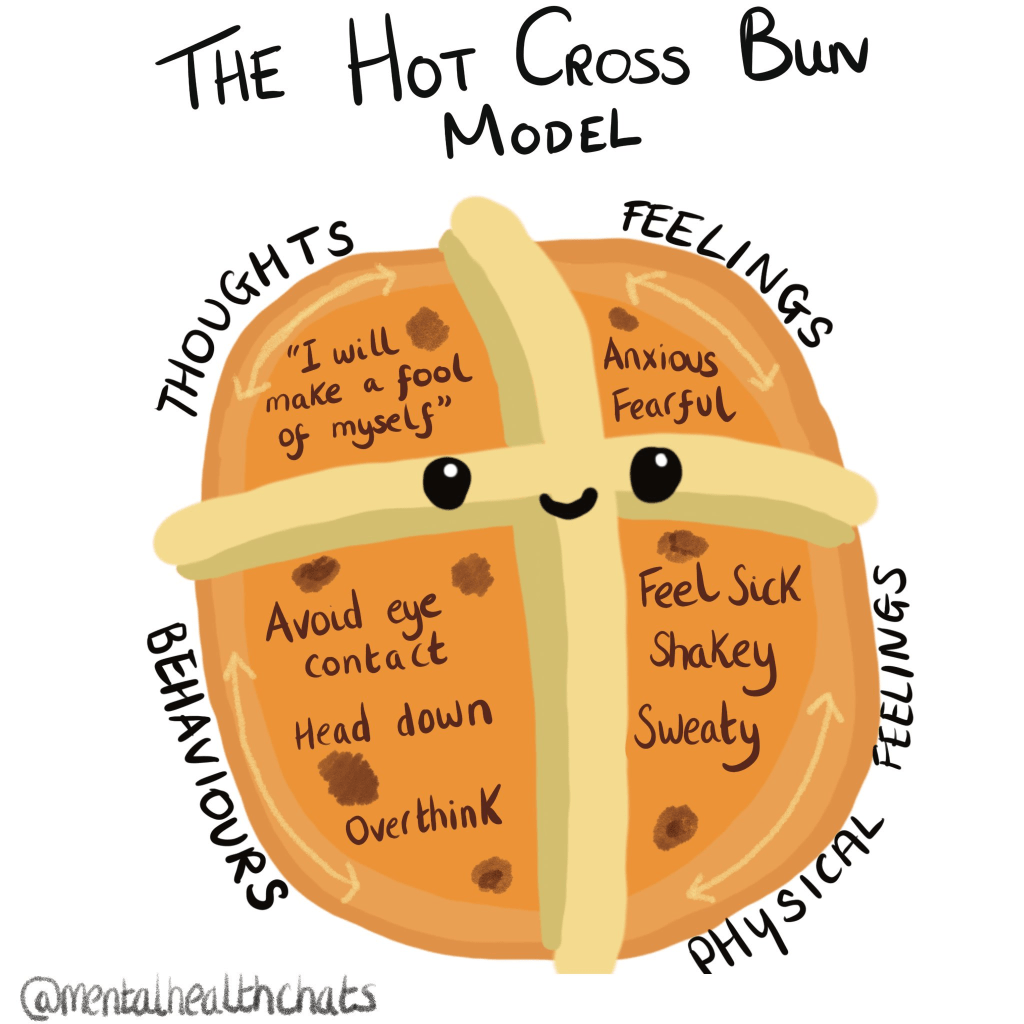

Language choices (down to the word) can make an incredible difference to the way a message is interpreted. For example, saying ‘I need this from you by next Tuesday…’ is experienced entirely different to ‘We need to achieve this by next Tuesday. The expectation is that…’ When scripting an email, it feels doable for us to consider our language choices carefully, but this becomes much trickier in spontaneous communication e.g. a conversation. During these types of communication, leaders have to be far more responsive and rely on their instincts to recognise the ‘mood’ of the conversation. Again, there isn’t necessarily a formula for getting these spontaneous conversations ‘right’, but it may be useful to be aware of the below model, developed by Padensky (1995). This hot cross bun model, typically used in the context of clinical psychology, very helpfully highlights the interplay between individuals’ thoughts, feelings, behaviours, and physical feelings. Recognising the relationship between these, can potentially support leaders in truly unearthing people’s perspectives enabling them to truly see and hear those they lead. As Peter Drucker, quite aptly puts it: ‘The most important thing in communication is to hear what isn’t being said’ Peter Drucker

Communication for Professional Learning

Effective communication is also essential when designing and delivering CPD of any kind. Matt Abrahams, lecturer on communication at Stanford Graduate School of Business, offers some useful guidance on how best we can communicate during any form of presentation. He encourages speakers to:

- Help their audience feel comfortable by mastering one’s own anxiety. How? By recognising it, acknowledging it, and accepting that it’s something we ALL feel. This alone can minimise the impact that this undoubtedly has on us when addressing a room.

- Reframing your view of things by moving away from ‘trying to get it right’ towards ‘having a conversation’. By doing so, we shift the dynamic in the room away from transmission of information to an interactive conversation. From didactic to dialogic. From being told to collectively learning.

- By opening with a question to invite the audience into the ‘conversation’.

- Abrahams suggests structuring your presentation as an answer to a list of questions to again, move towards the dialogic.

- He also encourages speakers to be hyper-vigilant about the language that they use and to keep it simple. He encourages speakers to opt for simple language that unites, rather than language that creates a distance between the speaker and audience.

When crafting professional learning, we therefore may want to consider the following questions:

- What will my audience know at the end of the session that they didn’t before? Limit this to 1-3 things as not to cognitively overload our audience.

- What terms will I use? When will I define those terms?

- Why is this important for them to know? How will it impact them day-to-day?

- How will my audience feel when they leave this session?

- How will I involve my audience in the conversation?

Communication, like school culture, is messy, knotty, and heavily context considerate. It varies from person-to-person and situation-to-situation. Because of that, it can sometimes be scary to focus on this, amongst the billion other things leaders need to focus on. I would argue however, that it’s in the very small interactions of a few sentences or words, that trust and psychological safety are built. If we as leaders can accept that we won’t always get it right and be at peace with this, we can perhaps open up a conversation about what good communication does look like in our contexts. Perhaps by creating norms with other leaders, we can create a safe, consistent drumbeat of interaction within our teams, laying the foundation for a work environment that feels calm and consistent, where people feel truly seen and heard and where there is a deep and enduring sense of community.

Link for further exploration:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HAnw168huqA (Mark Abrahams Lecture)