Exercise can feel uncomfortable, unpleasant, and sometimes impossible. But as adults, we know avoiding it only leads to more problems later.

Now, let’s reframe that…

Disagreement can also feel uncomfortable, unpleasant and yes, sometimes impossible! However, while not every disagreement leads to positive outcomes, as school leaders, we recognise that avoiding honest conversations can often cost us far more in the long term: strained relationships, stagnation, and decisions made without the benefit of diverse perspectives.

Charlan Nemeth’s research into group dynamics and dissent, spanning from the 1970s to the 1990s, found that disagreement isn’t just helpful, it’s essential in many contexts. It encourages divergent thinking, improved idea generation and deeper analysis.

Her work also revealed something important for team discussions in schools: authentic disagreement (genuinely held opposing views) is far more effective than someone simply ‘playing devil’s advocate.’ This relies on a level of psychological safety that teams may lack. The conditions for such candour must be deliberately built for colleagues to feel genuinely safe when speaking up.

Of course, speaking up, especially when you’re the dissenting voice, can be daunting. As Stone and Heen note in Thanks for the Feedback, receiving feedback of any kind sits at the intersection of our ‘drive to learn and longing for acceptance.’ The same is true for giving feedback, particularly when it goes against the grain of group consensus or tradition. However, without that all-important psychological safety, dissent often alienates rather than drives constructive dialogue. In short-it’s a delicate challenge.

In school settings, staff may hold back from challenging a popular opinion, not because they lack ideas, but because they worry about how they’ll be perceived. Yet Nemeth’s work shows that minority views, even when quiet, have a lingering impact. They shape decisions subtly and over time. This challenges the idea that power rests with a small group at the top, questioning hierarchical models that keep it there.

Power and the School Staffroom

In schools, as in any organisation, power dynamics shape who feels safe to speak and whose ideas carry weight.

The Social Alignment Theory of Power (Fast et al., 2002) explains that people adapt their behaviour depending on how much influence they believe they have. In a school setting, this might mean that a newly qualified teacher stays quiet in a meeting, while a long-serving SLT member speaks freely. These dynamics are often unspoken but deeply felt and as leaders, we must pay attention.

Three Responsibilities for School Leaders

- Notice the dynamics in your team.

Who’s speaking? Who’s staying silent? And why? Pay attention to participation patterns in meetings and informal settings. - Use your influence purposefully.

Leadership isn’t just about being the loudest voice or final decision-maker. It’s about creating conditions where others can contribute confidently even (especially) when they disagree. - Distribute power deliberately.

Share responsibility. Rotate facilitation roles. Encourage staff to lead discussions or initiatives. Small structural changes can foster big shifts in confidence and agency.

A meta-analysis by Schaerer et al. (2020) found that while power can help individuals achieve their own goals, it often gets in the way of collective progress. Most school leaders won’t need academic data to recognise this; many have experienced the impact of a leader who dominates rather than fostering collaboration.

From Theory to Practice: Disagreeing Well in Schools

We’ve established that:

- Disagreement can be valuable in certain contexts.

- How we disagree matters.

- Power dynamics influence who feels free to disagree.

So how can school leaders build cultures where disagreement isn’t feared but welcomed?

1. Don’t Play Devil’s Advocate

Rather than performing opposition, express genuine thought. Try this:

“I think I disagree on this one…”

This phrasing balances humility, honesty, and specificity:

- “I think” suggests openness.

- “I disagree” is clear and respectful.

- “On this one” signals that you’re not oppositional by nature, just thoughtful in this moment.

2. Level the Playing Field in Team Meetings

It’s hard to remove hierarchy entirely but you can reduce its impact:

- Ensure all voices are heard, not just the confident or senior ones.

- Gently invite contributions from quieter team members.

- Rotate who leads meetings or shares reflections.

- Avoid symbolic power positions, like always sitting at the “top” of the table.

3. Pick a Lane and Be Honest About It

Leadership in schools involves an acknowledgement of power dynamics. Ask yourself:

Are you leading for your own advancement, or for something greater?

Progress for yourself and your community are not mutually exclusive. Effective school leadership requires balancing your own professional growth with the broader needs of the school, ensuring personal development strengthens collective progress. But how you balance those motivations and how they show up in your interactions matters deeply.

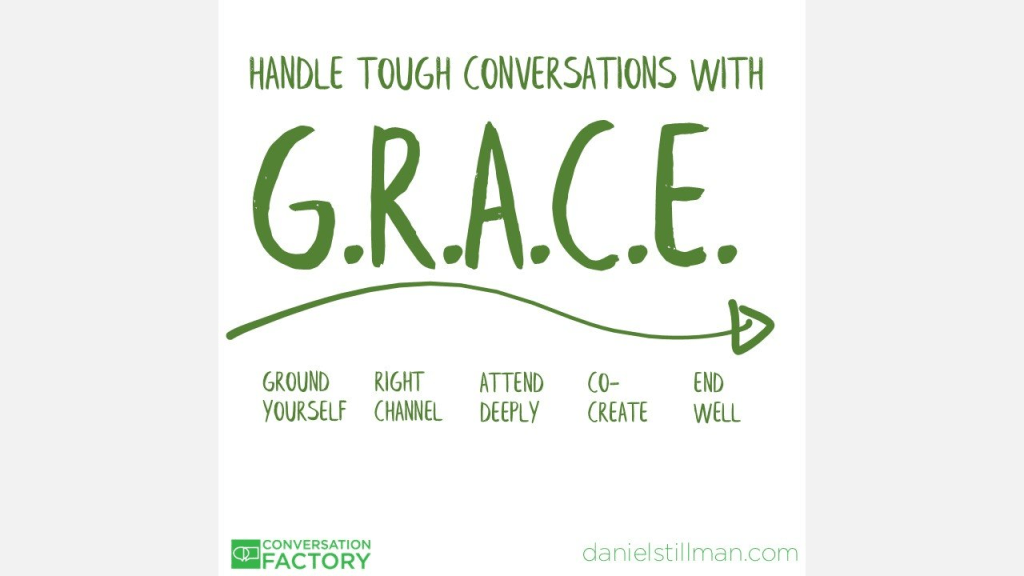

Practical Ways to Disagree with Grace in Education

Disagreeing with grace isn’t just about research or reflection. It’s about our daily practice in staffrooms, classrooms, and leadership conversations. Here are a few grounded reminders:

- Match the medium to the message.

If you’re raising disagreement online or via email, be respectful. Tone is easily lost, and sarcasm rarely wins people over. - Stay open.

Avoid gatekeeping. Resist the temptation of the echo chamber. Good ideas can come from anywhere: new staff, different departments, or external voices. - Allow people space to grow.

Give colleagues the grace to change their minds. We’re all learning. Assume good intent and leave room for development. - Model politeness.

It’s easy to overlook, but manners still matter. Courtesy builds trust and trust builds better teams.

Disagreeing in school leadership isn’t always comfortable, but it’s necessary. Like exercise, the discomfort is part of the growth. Avoiding it doesn’t make it go away. It just makes the problems grow in silence. Because in leadership, unchecked power can quickly turn into pique and that can quietly undermine the very purpose of what we’re here to do: lead learning, lead people, and lead with integrity.

The Importance of Language: Framing Professional Conversations

Finally, it’s worth reflecting on the language we use around conflict and conversation. The word ‘disagreement’ can sometimes carry connotations of opposition or conflict, which might unintentionally discourage open dialogue. Instead, terms like ‘debate,’ ‘professional discourse,’ or ‘collaborative inquiry’ might better capture the spirit of constructive and respectful exploration of ideas that we want to cultivate in education. Debate is a skill. It is rooted in respect, evidence, and active listening that can be developed and valued across the sector. By framing our conversations this way, we encourage a culture where diverse ideas are rigorously but respectfully examined, supporting continuous learning and fostering a culture of growth, not division.